India has consistently opposed data exclusivity in trade negotiations.

New Delhi:

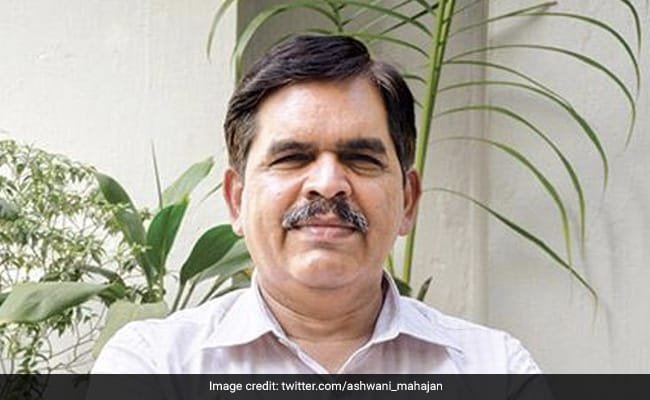

Implementing data exclusivity could impact India’s pharmaceutical and agricultural sectors and public health, Ashwani Mahajan, the co-convenor of Swadeshi Jagran Manch, has said. In a blog post on data exclusivity, Mr Mahajan said the topic has been a point of contention since the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT).

Data exclusivity refers to the period during which a manufacturer cannot rely on existing data to support the approval of a generic or similar product. This prevents companies from introducing generics or biosimilars until the exclusivity period expires. As a result, the introduction of affordable alternatives is delayed, directly impacting the consumer, particularly in sectors like pharmaceuticals, where price reductions post-patent expiry are critical to ensuring affordable access to medicines.

Mr Mahajan says India’s pharmaceutical industry has been able to manufacture generic versions of medicines as soon as patents expire, often reducing the price of medicines by up to 90%. This has led to the establishment of government schemes like the PM Jan Aushadhi Kendras, where generic medicines are sold at discounted rates. The introduction of data exclusivity could put an end to these benefits, forcing consumers to pay much higher prices for medicines.

Despite the government’s clear stance against data exclusivity, multinational corporations (MNCs) and foreign governments continue to push for its inclusion, particularly through Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). While these efforts have been largely unsuccessful for over two decades, recent developments signal a renewed push that could harm domestic industries and public health.

One example, Mr Mahajan points out, is a November 4, 2024, order from the Department of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare. “As per this order a committee has been constituted to explore and examine the provisions related to data protection for agrochemicals. This order, has been issued on the pretext, ‘to study the requirements of regulatory data protection and global best practices on data protection with the intent to introduce new molecules and pesticides that have no alternatives aimed at protecting major crops from these losses due to new invasive pests and diseases’,” he writes.

India has consistently opposed data exclusivity in trade negotiations. Its withdrawal from the 2019 Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) was partly due to provisions seeking to “extend pharmaceutical corporations’ patent terms beyond the usual 20 years,” says Mahajan, adding that such measures threaten access to affordable medicines.

“In many of the FTAs on table, including UK, USA and EU, this issue of data exclusivity is definitely, a cause of major concern for Indian industry, especially pharmaceutical and chemicals,” he writes in the blog.

On the official position, Mr Mahajan says that government memorandums, including a 2015 note on the Pesticide Management Bill, have consistently flagged data exclusivity as “TRIPS-plus” and if “this provision is extended to agro-chemicals, there will be pressure from MNCs to extend the same to pharmaceutical products also,” which would delay generic drug entry and inflate prices.