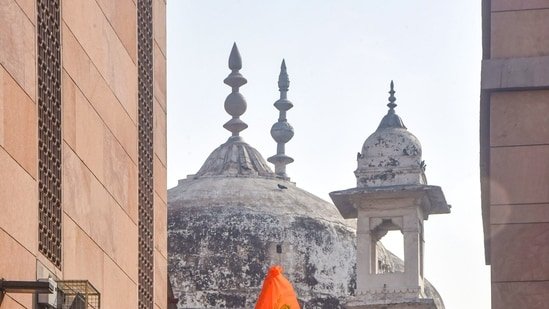

Lawyers for the Hindu litigants in the Gyanvapi Masjid case claimed Thursday that a survey by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) has found that a large temple existed at the site of the mosque in Varanasi. The ASI survey reportedly found inscriptions and other material evidence to suggest that a temple existed before construction of the mosque and concluded that the former was destroyed in the 17th century, a period that coincides with the reign of Mughal emperor Aurangzeb. The custodians of the mosque argue that the structure was built 600 years ago and even repaired during the time of Akbar. The ASI’s survey is likely to strengthen the claims of the Hindu side and help build public opinion in its favour.

Two questions arise in this context. First, what is the import of the Gyanvapi survey since the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991, a central law passed by Parliament after demolition of the Babri mosque, insists that the religious character of a place of worship (Ayodhya was exempted) shall continue to be the same as it was on August 15, 1947 and that no person shall convert any place of worship into one of a different denomination? Second, to what extent can history and archaeology be deployed to settle disputes related to faith? The Hindu litigants in Ayodhya once held the position that courts can’t adjudicate on matters of faith, whereas the Muslim side reposed faith in the judiciary. However, it was the SC that brought closure by ruling in favour of the Hindu side.

In a country like India, with its complex history of migrations, invasions, and conversions, deploying history and archaeology to correct historical “wrongs” and grievances will be a fraught project. History’s ghosts are best left untouched so that the State can focus on delivering material prosperity rather than mediating religious claims. This is the logic that underlies the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991, which has been challenged in the SC. In 2019, the Court indicated that the case could be referred to a larger Constitution bench. However, there has been little progress since. The Court has also not ruled on the maintainability of the Gyanvapi suit. Meanwhile, the lower judiciary has allowed interventions in Varanasi and Mathura that go against the spirit of the Places of Worship Act. An early resolution by the SC in the challenge to the Act would help clear the air on the matter and draw the line for the lower courts in cases challenging the character of religious places. Delays vitiate the atmosphere and peaceful resolutions become difficult, as in Ayodhya where prolonged litigation led to the hardening of positions and showdowns with devastating consequences.

Meanwhile, the political ground may have shifted decisively in favour of Hindu claims to contested sites. It took the rath yatra by BJP leader LK Advani in 1990 to bring the Ram Janmabhoomi campaign to the centre stage of national politics and lifted the BJP to the pole position. In the late 1990s, the BJP was forced by allies to hold back its temple agenda and wait for closure in the courts. Today, the momentum is with Hindutva politics, although litigation seems to be a preferred route for parties. Which is why the apex court’s stance will have broader implications.

Continue reading with HT Premium Subscription

Daily E Paper I Premium Articles I Brunch E Magazine I Daily Infographics